Yelitsa Jean-Charles

As a young girl, do you remember playing with a doll that did not look like you? Do you remember combing her long blonde hair and dressing her plastic nude skin with endless Velcro outfits?

You cherished her as if she were your friend. But when the time finally came she could not explain to you why you were disliked based on your dark skin, why the White boy in class said you were ugly and the Black boy agreed, or why you burned yourself with the hot comb because your hair didn’t mold to White authority.

She was silent during those times of confusion— when you began to hate yourself because it seemed like others shared the same sentiment. You hadn’t yet formed a defense mechanism that produced self-love, hadn’t yet found your sistahs who could empathize with you, hadn’t yet learned that you can be both Black and beautiful.

Talking about hair and beauty becomes a community bonding experience for many women of color. Many hours can elapse and one can find the conversation still as energetic as it first began. This experience can be seen therapeutic as women share knowledge of new hairstyles, products, and experiences of distaste for their own natural, curly, kinky hair. These are the kinds of conversations that Yelitsa Jean-Charles continues to shed light on by reinventing an everyday childhood product.

I met Yelitsa at the 2015 Young, Gifted, & Black Conference at Smith College, and had the pleasure to hear her speak about the passionate work she does.

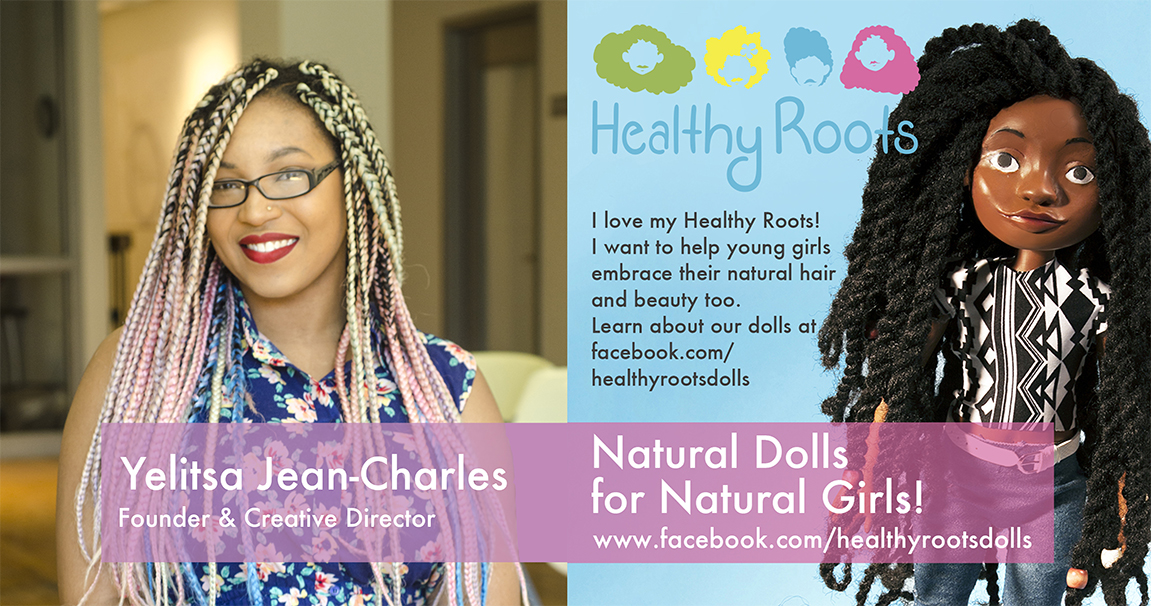

Jean-Charles is an unapologetic artist and a visual activist who recognizes the impact art has on challenging systematic injustices within our society. She uses her art to create a space for young girls of color to love their roots and the culture that accentuates it. While currently fulfilling her BFA in Illustration with a concentration in Gender, Race & Sexuality Studies at the Rhode Island School of Design, Jean-Charles was accepted as a 2015 Brown Social Innovation Fellow for an artistic venture that would have a positive impact on African-Americans and the Diaspora. Healthy Roots, a toy company whose dolls accurately represent women of the African Diaspora, features four different cultures: African-American, Nigerian, Haitian, and Pacific Islander/Afro-Brazilian.

These dolls are unique because they come in different skin tones, facial features and hair that can be styled like real natural hair. They are equipped with a storybook titled Big Book of Hair that teaches young Black girls how to care for natural hair step-by-step. Not only do young girls have the opportunity to play with these dolls, but they can learn about Africa as an existing character, allowing them to understand their identity as culturally rich.

Yelitsa’s artistic ventures have shown success, but believing in her passion has not always been easy. Although Jean- Charles’s parents told her to “be the best”, they did not easily see visual art as a stable career. Still, Yelitsa chose to pursue art, and made sure that she would be recognized. Yelitsa has refused to let others downplay her accomplishments, she states, “Even if I wasn’t a person of color, I would push myself to work harder”. Her personal accounts of racism reveal that when a group is constantly being downplayed and mis represented, internalized self hatred can grow. Therefore visual representation becomes even more essential.

So, what’s wrong a Black Barbie? Why does our consumption of a plastic doll even matter? It’s like painting the face of White Barbie and receiving an A for effort; it does not actually represent the unique beauty of Black and Brown features. Thus, Healthy Roots’s dolls challenge, and in my opinion outshines the one-dimensional Black Barbie, which still exemplifies Eurocentric beauty ideals by maintaining White Barbie’s hair and facial features.

It works to diversify the visual representations of women of the African Diaspora. It dismantles notions of the White Barbie as the “right” or “default” representation of female beauty and identity. Yelitsa critiques how young girls are being forced to “appeal to the standards of Barbie”, with Black girls being pushed to play with white Barbie as a default because of the lack of diverse toys. She asks, “Will they ever give a White girl a Black doll?” That question still lingers. Nonetheless Healthy Roots’ dolls are certainly not a frivolous innovation, but a politically-charged force that gives young girls the power to choose and to align with representations that looks like them.

Yelitsa recognizes that the doll we play with matters.

Although the Healthy Roots Project is focused on young girls of color, Yelitsa wants to emphasize that it is not just a person of color issue, but an issue of misrepresentation and lack of diversity that affects us all. She advocates that “diversity and representation matter because they combat all types of racism and expose people to other’s identity; this exposure allows for people to understand others”. Therefore, people should view this project as a way to expose institutionalized and internalized racism, colorism, and media abuse, while also advocating self-love.

Yelitsa’s artistic venture understands one group’s struggle as ongoing and interconnected. She inspires us to challenge these existing structures of injustice by creating an alternative, a representation of us, from us. To find out more about Yelitsa’s work and activism check out her Healthy Roots Dolls Facebook campaign: https://www.facebook.com/healthyrootsdolls and tumblr page: blackgirlatrisd.tumblr.com.