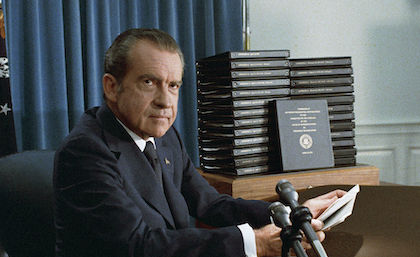

Richard Nixon. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

[From The Archives]

Richard Nixon feared dictator Idi Amin—whom he referred to as an “ape”— would “slaughter” 7,000 Britons living in Uganda and he instructed National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger to dispatch a top U.S. general to London to discuss a possible NATO operation to “evacuate” the U.K. nationals.

There are no details about what Kissinger ultimately conveyed to the general or what he discussed with NATO but there are hints that there may have been plans for regime change in Uganda.

Earlier in the year, hundreds of thousands of people had been massacred in Burundi by the army and Nixon told Kissinger he feared similar killings would occur in Uganda.

Amin, who had deposed President Milton Obote the previous year, had given 90 days to Uganda’s Asian community totaling about 80,000, to leave the country. Many had been in the country for generations and the Asian population dominated Uganda’s retail businesses, commerce, and trade. Amin claimed they had “milked the cow without feeding it.”

During colonial rule in East Africa—Uganda, Kenya, and what was Tanganyika, now Tanzania—the British had promoted the Asian community as the local capitalist, forming a buffer between Europeans and Africans. The Africans were denied access to credit, and barred from certain industries. Amin exploited the resentment which had been the legacy of this colonial policy and some segments of Ugandan society welcomed the expulsion of Asians. Amin awarded many of the abandoned businesses to his cronies. Amin also said he wanted to teach the British a “lesson.”

Relations soured with Britain and the U.S. after the expulsion of the Asians. Many migrated to the U.K., Canada, and the U.S.

The British were alarmed about the fate of 7,000 Britons in Uganda. Kissinger told Nixon that the State Department had snubbed London after the British had reached out, seeking a secret meeting to discuss contingencies. “Screw State!,” Nixon told Kissinger. “Stateʼs always on the side of the blacks. The hell with them!”

Nixon, who was notorious for referring to African Americans with the N-word, as was later revealed by recordings of his White House conversations, at one point referred to Africa as “these goddamn countries” and implied the leaders were cannibals. This was almost half a century before another Republican president, Donald Trump, made his infamous “shithole countries” comment. Nixon was of course much better educated and more knowledgeable about foreign affairs than Trump. He expressed racism toward Africans yet said he didn’t believe African leaders should be able to commit massacres with impunity.

The 15-minute conversation between Nixon and Kissinger occurred on Sept. 24, 1972, at Camp David, records show.

Nixon told Kissinger that he’d been following press accounts of the recent massacres in Burundi and feared similar killings in Uganda. In Burundi the Tutsi-dominated army had slaughtered an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 Hutus, between April and August 1972. Burundi, like its neighbor Rwanda, had been bedeviled by ethnic combustibility between its minority Tutsi population and the majority Hutus.

“Well, I just canʼt understand why we havenʼt had them before,” Nixon said, at one point, apparently surprised that mass killings hadn’t already occurred in Uganda under Amin. “You know, like that thing on Burundi. Now I want Stateʼs ass reamed out on that for not—” Kissinger interrupted Nixon, who went on to express disappointment that the State Department hadn’t sent the White House a memo about the Burundi genocide.

Nixon described how the West always took heat from liberals for involvement in distant conflicts on behalf of “people far away.” He pointed to the heat the U.S. was getting for its role in Vietnam, and also recalled Britain’s acquiescing to Nazi Germany’s demands when Czechoslovakia was threatened.

“Donʼt you really feel—I mean, and just be—letʼs be totally honest. Isnʼt a person a person goddammit?” Nixon said to Kissinger. “You know, there are those that, you know, they talk about Vietnam, these people far away that we donʼt know. And you remember that poor old Chamberlain talk about the Czechs. That they were far away, and ‘we donʼt know them very well.’ Well now, goddammit, people are people in my opinion.” British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was later faulted for the “Munich Betrayal” that led to the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, Hitler’s invasion of Poland, and the beginning of WWII.

Nixon was also apparently angered by what he saw as a double standard. He told Kissinger the State Department was always sensitive to protests against U.S. interference overseas. “…every time that anybody else gets involved—you know, every time that—one other individual or us, and you have a little pressure group here, State goes up the wall,” Nixon said. “But Iʼm getting tired of this business of letting these Africans eat a hundred thousand people and do nothing about it.”

“I know what the Uganda thing is. What it is—itʼs just like Burundi,” Nixon added, again voicing displeasure with the State department. “The State—Newsomʼs attitude—the attitude of State is to be for whatever black government is in power. Is my—right or wrong?”

“One hundred percent right,” Kissinger responded.

Nixon recalled his past differences with the State Department over the Nigerian civil war of 1967-1969. “Now frankly, I was on the side of the Biafras then. Not just—not because of Catholics. And you were too. Not because of Catholics but—State was on the side of the Nigerian government. Why? Because they said, well, ‘all the other governments would come apart,’” Nixon said.

Nixon suggested that Africa would be better off having fewer countries, which, ironically, is what Pan-Africans like Kwame Nkrumah—whom Nixon also insults—had advocated and worked for, before he was deposed in a 1966 coup in which the U.S. played a role. “Well frankly, Iʼm almost to the opinion myself—and this is far down the road, we need a new African policy. But first of all, we shouldnʼt have 42 ambassadors to these goddamn countries,” Nixon said. “In the second place—I mean, you know, at the same level as anybody else—in the second place, my own view is that some federations down there are what are needed, or something.”

“I donʼt know. But, but we can talk about that later,” Nixon continued. “But at the present time, looking at Uganda, of course weʼve got to help those 7,000 people. I asked Rogers about this when we met with Bush.” William P. Rogers was Nixon’s Secretary of State; George H.W. Bush, a future president, was the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, and father of another future president, George W. Bush.

Kissinger was also concerned that any leak of a possible U.S. plan could harm Nixon, and also that if Amin suspected any possible invasion he’d start slaughtering the Britons. The two decided to send a civilian from the Defense Department to Uganda, as the overt face of the evacuation mission; meanwhile, Nixon instructed Kissinger to send Gen. Andrew Jackson Paster, commander in chief of the U.S. European command, and supreme allied commander of NATO forces, to meet with U.K. and NATO officials. “…look, NATOʼs sitting over there on its ass doing nothing anyway,” he said. “Why donʼt we tell Goodpastor (sic) to get all the assets for the purpose of evacuation that we can have? Right?”

“In other words, NATO assets. Letʼs let the NATO countries do it,” Nixon added. “We canʼt have a British slaughter down there. The British have got enough problems.”

“Absolutely, and itʼs a—it would be a disgrace anyway,” Kissinger said, agreeing.

“Isnʼt it awful though what these—that this Goddamn guy at the head of Uganda, Henry, is an ape,” Nixon told Kissinger at one point, referring to Amin.

“Heʼs an ape without education,” Kissinger said.

“Thatʼs probably no disadvantage. I mean that,” Nixon added, and Kissinger laughed, according to the transcript of the conversation.

“I mean, you figure that that asshole that was the head of Ghana had a brilliant education in the United States,” Nixon continued, referring to Ghana’s Nkrumah. When Ghana held its independence celebration in 1957, Nixon, who was then vice president under Dwight Eisenhower, represented the United States.

“Thatʼs right,” Kissinger said.

“I mean, so, letʼs face it—no, no, what I mean is heʼs, heʼs—he really is. Heʼs a, heʼs a prehistoric monster,” Nixon said, of Amin.

“But, but the same with Burundi. But can—I really, really got to shake up the Africa—while all the departments—but the Africa department at State, Henry, is a disgrace,” Nixon continued.

“When I receive those—you know, I receive ambassadors. All I receive is Africa—three out of four every time are African ambassadors. Theyʼre nice little guys, and so forth and so on, but they donʼt add anything,” Nixon said.

“Yeah,” Kissinger agreed.

“I mean, it—and, and State just treats them—I mean, what, what do you think theyʼre up to? What is our African policy? Will you tell me?” Nixon said.

Kissinger told Nixon that he’d removed a paragraph “which was an all-out attack on South Africa” and Mozambique from a speech Secretary of State Rogers was to have made at the U.N.

“No sir,” Nixon said, agreeing with the move. “Never. Never.”

At the time South Africa was still ruled by an oppressive white minority regime during apartheid, and Mozambique had a white Portuguese colonial government.

“…and they are anti-white in Africa,” Kissinger said. “They are, they are obsessively liberal. But you donʼt hear them say a peep—you, you know, when one of these governments is, is not fully democratic that they donʼt like, they scream. But when they murder people in Burundi, when thereʼs—get a fellow in, in Uganda has a reign of terror, you donʼt ever get a protest.”

“Yeah,” Nixon said. “Now, on, on Burundi, State underestimated, and I know that your people were using it. Do you use the figure 100,000? I understand itʼs 200,000.”

Nixon asked Kissinger to invite the Belgian ambassador for a White House meeting to get an estimate of how many people had been killed in Burundi, which was once a Belgian colony. “I want to know what happened in Burundi. And I want the real cold-cock on that. Just, just you know, for future reference,” Nixon said. “Because in these African governments and the rest, the idea that weʼre going to stand still on the ground that any African government that was—overthrew a colonial power thereby becomes lily white by our, by our standards and thereby beyond criticism is ridiculous. This damn double standard is just unbelievable.”

Nixon’s words suggests that the NATO role in the new Africa approach he contemplated may not have been passive. In any case, there was no NATO involvement in Uganda and eventually most American and British citizens left the country. The U.S. closed its embassy in Uganda on November 10, 1973.

Nixon’s administration was incapacitated by the Watergate scandal; Amin reputedly sent him a “get well” telegram wishing him a speedy recovery from Watergate. Nixon resigned on Aug. 9, 1974, to avoid impeachment. He died in 1994.

The U.S. embassy in Uganda wasn’t reopened until after Amin was overthrown in 1979, ending his regime of terror; Uganda is once again ruled by a maniacal dictator. Amin died in 2003, in exile, in Saudi Arabia.

Kissinger is now 97 years old. There was no response to an e-mail message from Black Star News seeking comment, sent via the contact information on his website.

The transcript of Nixon’s conversation with Kissinger is available on this link to the historical site of the State Department, which contains documents related to U.S. foreign affairs dating to past centuries.

Follow the author @allimadi

Gen. Idi Amin. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Henry Kissinger. Wikimedia Commons.