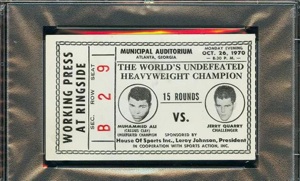

Press pass from Ali’s historic comeback bout. Image from www.bidami.com Auction site

[From The Archives]

Half a century ago, on June 20, 1967, boxing’s heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali — aka Cassius Clay – was convicted of refusing induction into the U.S. military.

Ali, 25, had won a gold medal at the 1961 Olympics and captured the heavyweight championship in 1964, the same year he became a Muslim. An all-white jury in Houston convicted him, a descendant of a runaway Kentucky enslaved African, after deliberating for all of 21 minutes.

After the conviction, Ali was barred from professional boxing. However, three years later, on Monday, October 26, 1970, he had his first professional fight at Atlanta’s Civic Auditorium. The fight drew 5,000 attendees with ringside seats going for $100 ($650 in 2017 dollars) and over 200 theaters in the U.S. and Canada screened the fight live. In the showdown, “The Greatest” took on Jerry Quarry, the “Great White Hope” and the No. 1 ranked contender; the fight was called in the 3rd-round with Quarry suffering a bleeding cut above his left eye. Ali was back.

After the bout, a jubilant, all-night celebrator party was held at the swank Regency Hyatt Hotel and everyone who was anybody in the African-American community was proudly in attendance, sporting their grandest finery. Boxing historian Bert Sugar later noted, “It was the greatest collection of black money and black power ever assembled until that time.” He added, “Right in the heart of the old Confederacy, it was Gone With the Wind turned upside-down.”

Often forgotten, the post-fight festivities were marred by one of the greatest con-artist scams in American history. Three black gangsters in ski masks staged a clever, invitation-only party for between 100 and 200 high-flying guests, welcoming them to an up-market house for a night they would never forget. Instead of champaign and caviar, party-goers were greeted by bandits sporting pistols and sawed-off shotguns. The dumb-struck revelers were separated from their cloths, cash, jewels, mink coats and other valuables. Adding insult to injury, they were escorted at gun point to a very crowded basement and stacked, unceremoniously, one on top another with little space between them. One of the invited guests was Muhammad Ali’s own father, Cassius Clay, Sr.

This half-century old episode in urban history is worth recalling because it reveals an often-overlooked episode in Ali’s long and honorable life. Most disturbing, it reveals how smart conmen of whatever race can take advantage of a moment of community celebration to plunder the best of public intentions. Not surprising, shortly after the robbery, some of the apparent conmen themselves were found dead, killed execution-style, victims of their well-executed scam. In this case, crime surely didn’t pay.

Eight months after the fight, on June 28, 1971, the Supreme Court, in Clay v. U.S., unanimous overturned Cassius Marsellus Clay’s 1967 conviction for draft refusal. The Court found that Ali, based on his Muslim faith, had been illegally barred from being classified a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War.

Ali had been officially classified “1-A,” eligible for the draft. But on April 28, 1967, he refused to symbolically step-forward and take an oath of allegiance on religious grounds, insisting that he was a Muslim conscientious objector and opposed to the war. “War is against the teachings of the Koran,” he insisted. “I’m not trying to dodge the draft [but] we don’t take part in Christian wars.” He also stated, “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” and supposedly declared, “no Vietcong ever called me nigger.” The Court determined “that [Ali’s] beliefs are founded on tenets of the Muslim religion as he understands them.”

The federal government had prosecuted Ali as a draft-dodger and he was sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000 and barred from leaving the country. Free on bail as he appealed the conviction, Ali was effectively barred from professional boxing, his chosen profession. The New York Boxing Commission, the World Boxing Association and other groups stripped him of his championship title and banned him from the ring.

His stand cost him dearly. As he contested his conviction, he struggled to made a living by hustling his story, appearing on TV talk shows and giving speeches at black colleges and universities. At a talk at Atlanta‘s Morehouse College, Harry Pett, a white local businessman, introduced himself to the former champ and proposed holding a major boxing event in Atlanta to bring Ali back to the ring.

Pett had connections to a sports-marketing firm, House of Sports, Inc., and thought there was a loophole in state and local laws so he could pull off what others hadn’t. More than 50 locales denied a license to hold the fight. In the summer of 1970, Pett contacted Leroy Johnson, an Atlanta state senator, and offered him a deal he couldn’t refuse: “If you can provide the venue, we can get a contract with Ali.”

Johnson was the first African-American elected to the Georgia legislature since 1907 and the first elected to the Senate since 1874. Recalling the fight in 2015, he said, “The thing that energized me was that the New York boxing commission said he’d never fight again in this country.” He added, “To me that became a challenge, a challenge against the system.”

Before the come-back Ali’s last professional fight was on March 22, 1967, at Madison Square Garden, against Zora Folley, who he knocked-out in the 4th round. The terms of the proposed Atlanta fight were more than fair. Ali was reportedly offered $200,000 (about $1.45 million today), against 42.5 percent of the revenues; Quarry was to get $150,000 guaranteed, or 22.5 percent of the revenue. If Ali won the bout with Quarry, it would be a first-step to him regaining boxing’s heavyweight championship.

On the night of the match-up, Atlanta was on its toes; fears of a race war were in the air. Lester Maddox, an arch segregationist, was governor; segregationists and veterans’ groups protested the fight; and racist commentators warned Black Muslims were going to shoot Quarry in the ring. Black Muslims protected Ali, fearing a racist attack. Atlanta was a powder-keg.

But for those inside the Civic Auditorium for the fight, the joint was jumping. One of those in attendance was Stan Sanders, an attorney and the first African-American Rhodes Scholar. “I had never seen that kind of convocation of African-Americans,” he later exclaimed. “There were the civil rights leaders—I remember running into Whitney Young in the lobby—and the prominent businessmen, and there were the famous African-American athletes.”

“But,” Sanders added, “there were also the hustlers and gangsters, with names like Sacramento Joe and Detroit Slim, and [the] pimps and the drug dealers were dressed better than the chicks.” They were outfitted in mink and ermine coats, with bejeweled fingers and necklaces.

George Plimpton was also dazzled by the well-armed Harlem peacocks who travel in expensive Cadillacs with body-guards. He noted, “I’d never seen crowds as fancy, especially the men – felt hatbands and feathered capes, and the stilted shoes, the heels like polished ebony, and many smoking stuff in odd meerschaum pipes.”

Pee Wee Kirkland, a notorious New York street-yard basketball legend and drug dealer, attended the event. “We went down to Atlanta in a fleet of cars—something like 25 cars, tailgating one another,” he recalled. He proudly added, “I bought 500 tickets for the fight, all ringside, because I thought it would be real good if a lot of people from Harlem that I grew up with was able to see Ali in ringside seats.

Following the victory, revelry filled the city. At the Hyatt, everyone who was anybody in the black community was proudly in attendance. Among the notables were Arthur Ashe, Julian Bond, Julian Bond, Bill Cosby, Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King, Diana Ross and Andrew Young. Black gangsters from New York, Washington, Baltimore and Detroit joined in the festivities, celebrating Ali as one of their ow

Days before the fight took place, engraved invitations to a special party were left under the doors of hotel guests. They were discretely handed-out at the fight and at the Hyatt celebration. It announced that “Fireball” was throwing a birthday party for “Tobe” at 2819 Handy Drive in the Collier Heights section of the city’s West End. This was to be a special celebration of Ali’s victory — it was the scam described above.

The house was owned by Gordon (Chicken Man) Williams, a local lottery hustler, who claimed he and his girlfriend, Barbara Smith, were victims of the same gang of thieves. After taking their ill-gotten haul, the desperados fled by car, taking Smith as a hostage who was shortly released. It was a scam in which not a shot was fired. The local officer in charge, Lieut. R. E. Nickerson, said intelligence gathered from an anonymous call claimed Williams staged the robbery “to repay the New York people” for a drug deal gone bad; Williams denied the allegation.

However, two days after the robbery, Williams was reportedly murdered by hit men. Months later, two of the alleged main suspects in the robbery were found shot execution-style in the Bronx. A New York detective, J.D. Hudson, said, “We said last fall it was a question of who caught up with them first — the police or the victims.”

Following the victory in Atlanta, Ali thundered back, with fights quickly booked in New York’s Madison Square Garden and other venues. In December, he KO-ed the Argentine heavyweight, Oscar Bonavena, and, the following March, Joe Frazier gave him his first professional loss. Four years later, Ali defeated Frazier and then went on to beat George Foreman in the much-promoted “Rumble in the Jungle,” reclaiming the title.

Sidney Poitier and Bill Cosby attended the bout and follow-up festivities, but were not caught-up in the robbery. Returning to New York, they teamed up to make two now all-but-forgotten feature films apparently inspired by the fight and heist.

Uptown Saturday Night (1974), directed by Poitier, is set in Atlanta and stars Poitier, Bill Cosby and Harry Belafonte. The movie follows the misadventures of two blue-collar buddies – Poitier and Cosby – searching the underworld for a winning lottery ticket worth $50,000 robbed from them at a local speakeasy.

Let’s Do It Again (1975), also directed by Poitier and set in Atlanta, is the tale of two blue-collar guys trying to raise money for a local charity, the Brothers and Sisters of Shaka. It’s a wild and wooly tale in which Poitier and Cosby fix a boxing match in New Orleans by hypnotizing the underdog, collect a lot of money and return home only to be pursued by gangsters lost money on the fight. To square the circle, the two protagonists stage another match and hypnotize both fighters who knock each other out.

Over the years, filmmakers have sought to bring the Atlanta events to the screen, but have yet to do it. Whether as a narrative or documentary film, it’s a great story – Ali’s return to the ring, how it was organized and with fight footage; Atlanta filled with racial tension and excitement; the grand post-fight celebration; and the festivities finale, the nefarious holdup.

It has a narrative arch made for the screen – whether viewed in theatre, on TV or on a mobile device – that only history can offer, illuminating a unique moment in America’s lost history.

David Rosen can be reached at [email protected]; check out www.DavidRosenWrites.com.

© David Rosen, 2017