By Jared O. Bell

Photos: Wikimedia Commons

In countless casual political conversations over the years, I have heard the principle of the “lesser of two evils” invoked, the quiet suggestion that voting is less an act of belief than a calculation of how much damage one is willing to tolerate. Alongside this logic is the familiar refrain that “both parties are the same.” Both frames are reductive and ultimately defeatist. They shrink democracy into a form of harm management rather than collective self-determination and condition citizens to expect disappointment as the price of participation.

While American political parties have increasingly come to resemble corporate entities that deliver policy downward along party lines and donor interests, democracy was meant to function in the opposite direction. Citizens were supposed to form political parties to articulate shared needs, shape public priorities, and influence the policies that govern their lives. That inversion, where parties now shape the limits of political choice rather than channel popular will, lies at the heart of the democratic malaise.

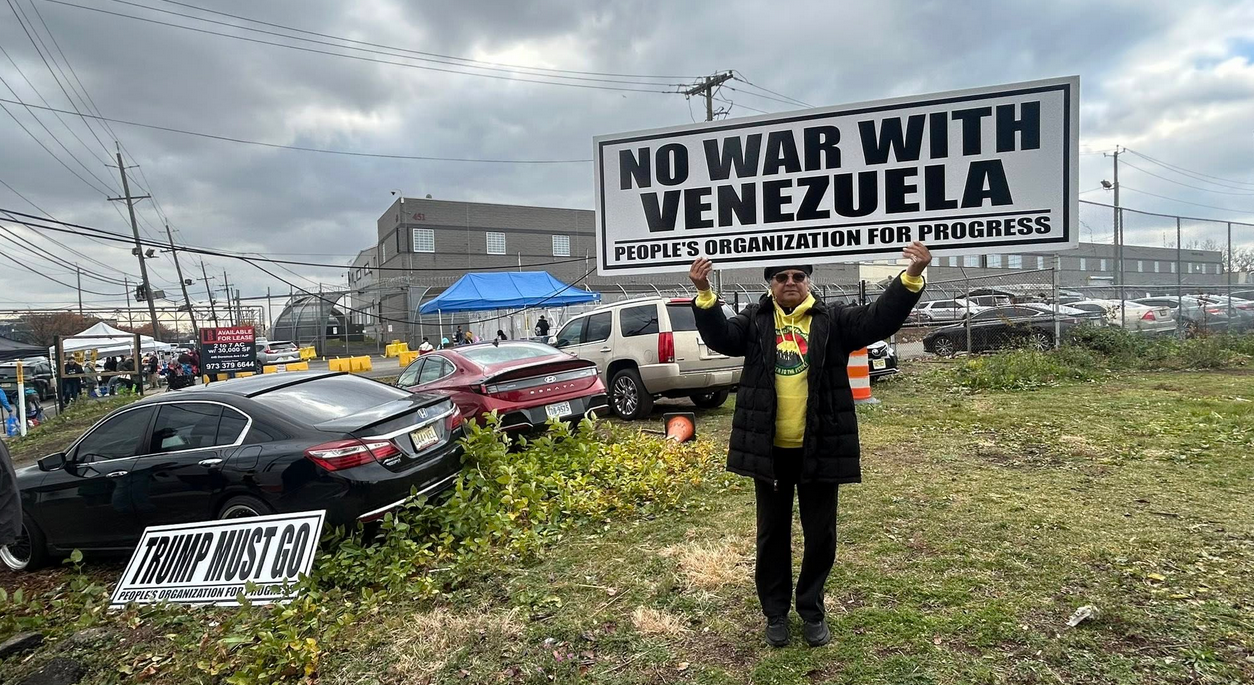

Although the United States does have third parties, their meaningful participation in state and national politics remains sharply constrained. There are more than 50 recognized political parties in the United States, according to national ballot-access records summarized by Ballotpedia, yet only a handful achieve sustained ballot access or public visibility. Among the most prominent are the Libertarian Party, Green Party, Constitution Party, Reform Party, and newer movements such as the Forward Party and the Working Families Party. Despite this diversity, third-party candidates are routinely framed as spoilers, accused of splitting votes between Democrats and Republicans, a dynamic rooted in the U.S. electoral system’s well-documented spoiler effect. This perception discourages voters from supporting candidates who may more closely reflect their values, forcing them instead to calculate the supposed realism of their vote within a system designed to marginalize political alternatives rather than accommodate them.

The irony is striking. For decades, the United States has promoted political pluralism abroad as a cornerstone of democratic development, particularly in the Balkans, former Soviet states, and other transitional societies, arguing that multiparty competition, broader access, and diverse political agendas strengthen democracy and prevent stagnation. Yet at home, the United States remains one of the least politically plural democracies among advanced nations, a reality reflected in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s classification of the United States as a “flawed democracy.” Under its winner-take-all, first-past-the-post electoral system, Democrats and Republicans hold nearly all state and federal legislative seats, with third-party and independent officeholders remaining exceedingly rare, effectively crowding out alternative voices.

Political pluralism, however, is not simply about the presence of multiple parties on a ballot. It underpins competition, accountability, and cooperation, three forces that are deeply interconnected. When genuine competition exists, parties face real pressure to deliver on their promises and respond to voter priorities. When elected officials know they can be voted out, they are more likely to govern in the public interest rather than defaulting to entrenched corporate or donor driven agendas. This competitive pressure is the foundation of accountability.

When competition is weak or constrained, accountability erodes. We increasingly see elected officials placing party loyalty above the broader interests of the country, insulated by partisan dominance rather than responsive to public mandate. The framers envisioned a system of three co-equal branches of government designed to prevent the accumulation of unchecked power. That balance is jeopardized when legislators are unwilling or afraid to break party ranks, declining to exercise oversight, treating impeachment as a partisan loyalty test, or privately acknowledging concerns about executive behavior while publicly defending it to avoid political retaliation.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, political pluralism fosters cooperation. In rigid two-party systems, governance becomes especially vulnerable to brinkmanship and zero-sum tactics, where compromise is treated as defeat and stalemate becomes strategy. With the most recent shutdown, a lapse in appropriations triggered a 43-day federal government shutdown from October 1 to November 12, 2025, making it the longest in U.S. history. During this period, roughly 900,000 federal employees were furloughed and about two million more worked without pay, while the shutdown stalled routine agency operations, disrupted statistical work such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics October jobs survey, and, according to Congressional Budget Office estimates and subsequent analyses, reduced quarterly GDP growth and caused several billion dollars in permanent economic losses.

In these moments, governance gives way to leverage, with critical public priorities, including healthcare subsidies and funding for health programs, drawn into budgetary standoffs and treated as bargaining chips rather than necessities. The destabilizing effects of shutdowns on health policy implementation, Medicaid administration, and insurance markets have been extensively documented by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

By contrast, in multiparty democracies such as Germany, coalition governance is the norm rather than the exception. No single party has governed alone at the federal level for decades, requiring parties to negotiate budgets, social policy, and crisis responses across ideological lines. Similarly, New Zealand’s mixed-member proportional system consistently produces coalition governments that rely on cross-party agreements, reducing the likelihood that any one faction can paralyze the state.

The larger question, then, is how the United States moves toward a more plural and functional democracy. The answer lies in institutional reform that expands access for third-party and independent candidates, including ensuring that all qualified candidates are heard equally in public debates and treated as legitimate contenders rather than dismissed in comparison to the two dominant parties. Electoral reform is also essential, particularly moving beyond winner-take-all systems. Ranked-choice voting offers one such pathway, allowing voters to rank candidates by preference and support alternative voices without fear of wasting their vote.

But institutional reform alone is not enough. A parallel cultural shift is required, one that moves away from the deeply ingrained belief that votes cast outside the two major parties do not count. Gallup polling shows that roughly six in ten Americans believe a third major party is needed, yet many voters still hesitate to act on that belief out of fear their vote will be futile. As long as participation beyond the duopoly is framed as wasted effort rather than democratic expression, political pluralism will remain constrained.

As the United States approaches the 2026 midterm elections and the 2028 presidential race, this conversation becomes urgent rather than abstract. What is increasingly undeniable is that the current two-party system is failing to meet the moment. The rise of insurgent movements across the political spectrum, from the Tea Party’s transformation into the MAGA movement on the right to the growing visibility of anti-establishment and progressive challenges on the left, including the rise of figures such as Zohran Mamdani in New York politics, whose electoral success is indicative of broader voter dissatisfaction with establishment-driven party structures, reflects a shared frustration with a political system widely perceived as unresponsive, exclusionary, and captured by entrenched interests.

Corporate driven politics is not delivering responsive governance, credible representation, or durable solutions. Institutional reform can widen access, and electoral innovations can reduce strategic voting, but neither will succeed without a renewed civic imagination.

A more functional democracy requires not only new rules, but a renewed commitment to political choice itself, one that recognizes pluralism not as a threat to stability, but as the very condition that makes democratic legitimacy real.

Jared O. Bell, PhD, syndicated with PeaceVoice, is a former U.S. diplomat and scholar of human rights and transitional justice, dedicated to advancing global equity and systemic reform.