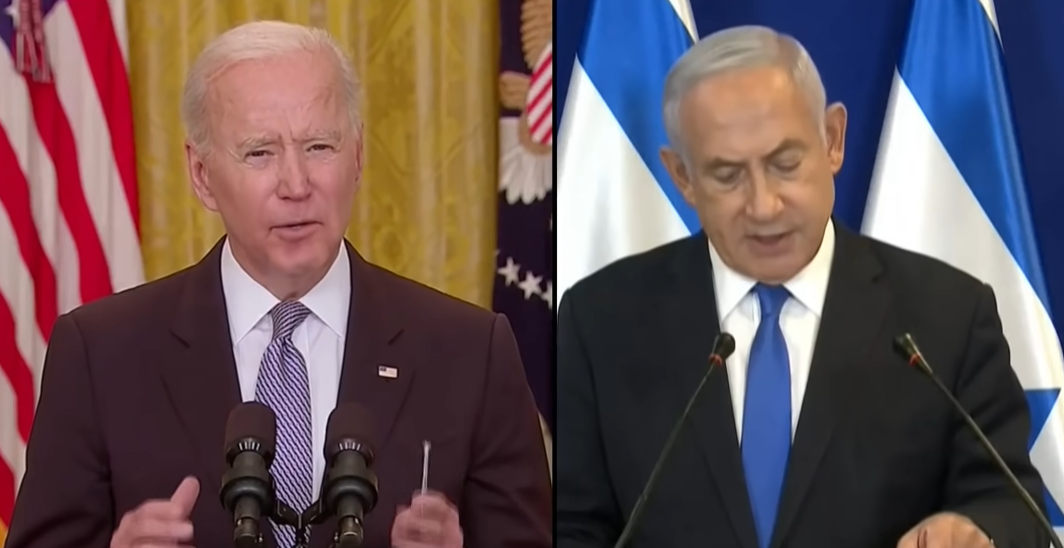

Left to right: Leonard Weir is on the left with the dark suit and bag on his shoulder. Bob Harris is in the center. Weir’s son is on the right with the white suit.

Boots Riley, the rapper and director of the film “Sorry to Bother You,” made news recently when he criticized Spike Lee’s portrayal of undercover police officer Ron Stallworth in Lee’s film Blackkklansman. According to Riley, Stallworth, who was made out to be a hero of the Black Power movement, was in fact a traitor due to his spying on Stokely Carmichael, who is credited more often than anyone else for starting the Black Power movement.

Riley’s critique brings attention to the issue of undercover police in Black radical organizations and the devastating effect the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) had on such organizations. In the mainstream narrative of the Black liberation struggle, the police officer is always the villain and nothing else. Not all cops in such groups were undercover or agents.

What is rarely discussed is the story of the militant Black police officer. There were above board police officers who were members of such groups who found a way to use their positions as cops to aid the Black liberation struggle. Such a history speaks to a more complex relationship between movement people and the police than is usually noted. It also helps us to understand how to improve the relationship between police and the Black community today.

Bob Harris of the Harlem chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was one such officer whose being a member of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) was known to the chapter. As Harris points out, he was already a member of Harlem CORE when he became a police officer, not the other way around. He joined NYPD directly after the 1964 Harlem uprising when organizations such as CORE were arguing the upheaval would not have happened if there had been more Black police officers, captains, and commanders of precincts. He fully participated in demonstrations, became the chapter’s treasurer and was in charge of security for Harlem CORE’s late chairman Roy Innis. Harris was considered so good at security for the chapter it was recommended by the national office for CORE chairman Floyd Mckissick that Harris’ example be replicated throughout the entire organization.

Although it was rare, there have been CORE members that were also above board police officers going all the way back to the 1940’s such as Lynn Coleman, co-chairman of Cleveland CORE, one of the few Black members of the Cleveland police department. Historian Nishani Frazier notes in her recent book “Harambee City” that he used his gun to protect CORE protesters from a White mob on at least one occasion.

In Brooklyn CORE, James Steward, who eventually became a transit officer, was still training in the police academy while a member of the chapter. That did not stop him from participating in some of his chapter’s most radical actions in the early 1960’s. Steward, along with fellow Brooklyn CORE member Bob Law, was also a member of the first Black Panther group in Harlem which came a few months before the Newton-Seale group in Oakland.

For an organization such as CORE, this should not be seen as strange. In many ways, members like Bob Harris were fulfilling the mandate of CORE – to help non-Whites get jobs in the predominately White municipal agencies such as the Board of Education, the Health and Hospitals Corporation, and the police.

CORE’s overall objective was to make America live up to its promise of democracy. As such, it had a “push and pull” relationship with law enforcement, in that while CORE recognized the need for law enforcement to do its job, CORE members risked arrest in pursuit of that goal.

Even during its civil rights phase, there were several members of the New York City (NYC) CORE chapters that physically fought the police at demonstrations despite the myth of pacifism that pervades the history of the Civil Rights movement. However, unlike groups like the Black Panthers that took a more militant stance in regards to law enforcement, and even though many CORE members will admit they would at times engage in similar rhetoric, according to Harlem CORE member Don Elfe, “We were not at war with the police”. Ironically, it was such protests that not only led to promotions for Blacks within NYPD such as Lloyd Sealy, the city’s first Black precinct commander, but to the hiring of more Black and Latino cops overall.

According to Elfe, the local precinct captain was even allowed to come up to the Harlem CORE office and hang out. Members just made sure not to talk business in front of him, especially in light of the fact they knew undercover officers had infiltrated the group. Several members have stated that some of these undercovers would secretly tell the Harlem CORE people who they were and that they were on the job.

That being said, the NYC CORE chapters might literally the next day be out in the streets fighting with Sealy and other members of NYPD, especially during CORE’s campaigns for community control of the city’s public school system. Ralph Poynter, for example, who worked with Harlem CORE punched four different cops in the face during these demonstrations at I.S. 201 in Harlem and did a year at Riker’s Island as a result.

Militant Black police officers could also be found in other Black radical organizations. Leonard Weir, also known as Leonard 12X Weir and later Humza Al-Hafeez, is noted as being the first member of NYPD to come out as a member of the Nation of Islam. Referred to as the “The most militant Black cop on the force,” he was a member of the historic temple Number 7 when Malcolm X was its minister. He was also the founder and head of the Society of Afro-American Policemen, a national organization of Black policemen and other city workers. Bob Harris was one of its vice presidents.

Weir referred to himself not as a Black cop but as a Black man who happened to be a cop. He argued the police did not have to be an occupying, oppressive force and saw his organization as a force to stop White cops from insulting Black women and beating Black children.5 Like CORE, he argued for more police that were Black to patrol the Black community as it would also help to lower incidents of police brutality.

While he received several citations as an officer and worked for the 1970 Knapp Commission on corruption within NYPD, Weir was also widely respected among the NYC Black militant community. Ali Lamont of Brooklyn CORE, whose chairman Sonny Carson was notorious for his physical clashes with police, remembers how they both walked the streets beside Weir during the upheavals after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968 to help keep the peace.

Such officers often pay a heavy price, though, as they may have not have been fully trusted by either side. Bob Harris eventually left CORE because others in his own chapter questioned his loyalty due to the fact he was also a cop. At the same time he was also repeatedly punished by commanders in his precinct and eventually pushed off the force while allowed to retire early with his pension and benefits.

Weir was also brought up on departmental charges several times. However, when he faced possible dismissal for insubordination and being late, his biggest support during his hearing came from the NYC Black nationalist community including members of Harlem CORE and the United Negro Improvement Association.

Police officers like Harris and Weir are significant because they set an example for Black and Latino police officers of today by demonstrating how it was possible to use their positions for the liberation of Black people. They represent a model for how officers can interact with the Black community, be respectful and still effective in terms of their jobs.

They not only created a space for Black cops and activists to communicate and work together, they helped create a space for Black and Latino police to voice dissent. By creating a blueprint for other Black cops to be militant they set a precedent for Black and Latino cops to be critical of the police.

You can see it in organizations such as 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement That Care and the Latino Officers Association. You can also see it in the rebuke by the National Black Police Association of the boycott against Nike called for by the National Association of Police Organizations due to Nike’s use of football player Colin Kaepernick in its new series of ads.

This kind of internal criticism is surely needed given the current climate. While outside pressure from such movements as Black Lives Matters and Stop Mass Incarceration is necessary, ultimately true change will have to come from within the system.

Such officers therefore represent a golden opportunity for police departments across the country to demonstrate they are responsive to the needs and concerns of Black and Latino communities. However, like Weir and Harris, such officers are instead treated as threats as seen in the case of the NYPD12 whose story was told in the recent documentary Crime + Punishment.

Finally, this history also challenges traditional narratives of the Black Power movement, showing it to be much more complex than most historians have noted.

It shows the movement to be much more than just a bunch of street dudes looking cool with afros, leather jackets and sunglasses shouting “Kill Whitey!” and getting into shoot outs with the police. It reminds us that the movement was multi-layered, from the street demonstrations, to efforts to transform existing government institutions in order to address systemic racism, to creating Black institutions for when the revolution ultimately was to come.