[Commentary]

The most noteworthy aspect of the series of popular demonstrations in response to the police lynchings of African-Americans that have occurred over the last few years may well be how few riots have taken place.

The term riot has been repeatedly invoked since the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin and, most recently, following the police killing of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, MD. The Baltimore riot took place between April 25th and May 3rd and consisted of sporadic looting, the setting buildings and cars on fire, and throwing of stones at police and firefighters.

Gov. Larry Hogan declared a state of emergency for Baltimore, called in the National Guard and set a curfew. It resulted in the arrest of 34 people, injury to six police officers with property damage estimated at $9 million by the Small Business Administrations, including the looting and fire bombing of a local CVS store.

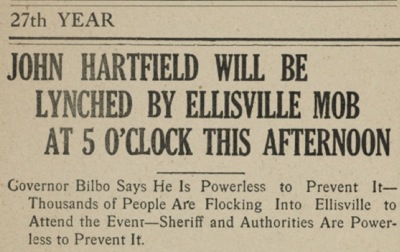

The term riot is now easily invoked to denote militant domestic protests, involving violence, and serves as the corollary to terrorism used to denote international non-state conflicts. The U.S. has witnessed two great waves of race-based riots: the first around the time of the World War I and the second amidst the Vietnam War.

In addition, innumerable mass disturbances, sometimes erupting into major confrontations, have taken place over the last century. One such local incident was the all-but-forgotten Harlem “riot” of 1935.

On the afternoon of March 19, 1935, Lino Rivera, a 16-year-old Black Puerto Rican youth, was caught stealing a 10-cent penknife from the Kress nickle-&-dime store on 125th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues in Harlem. The stores managers caught the youth, took back the knife and refused to press charges. But amidst his capture, a scuffle broke out, the youth bit the owners thumb and other scratch wounds were inflicted, leading to the loss of blood. An ambulance was called and, when it departed, rumors circulated that Rivera had been beaten and gravely wounded. A local cop took the boy out through the stores backdoor on 124th Street and, when a hearse parked nearby, rumors escalated, including that he had been killed.

The crowd quickly grew and the anger escalated. Demonstrators demanded the police present the youth; the police refused to comply. At 5:30 pm, as tensions mounted, the store closed and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia urged Harlem residents to remain calm. During the evening, the Young Communist League and the Young Liberators, a Black-activists group, mounted a protest demonstration that drew between 2,000 and 4,000 people. The Daily News reported, armed bands of [African-American] and white guerrillas, swinging crowbars and clubs, roamed through barricaded Harlem from 110th to 145th St., assaulting every person of opposite color to cross their paths, setting fires and smashing shop windows after a night of fighting .

According to the The Daily News, 27 people were arrested, numerous people were injured, three were seriously wounded and three people were killed. Among those wounded were newspaper reporters and photographers. The News failed to report that one of those the killed was Lloyd Hobbs, a 16-year-old African-American who the journalist Oswald Garrison Villard said had excellent standing and character. The youth, along with his brother Russell, had left a local movie theatre and were milling around in a small crowd at 128th Street and Seventh Avenue when a policeman shot him on suspicion of looting a shop.

The confrontations petered out by the next morning and order was restored. Long simmering grievances against White merchants and police mistreatment as well as the mounting toll the Depression was taking on African-American New Yorkers came together in the explosive rage over the apparent treatment of Rivera. Villard, writing in The Nation, noted: Thus the riot was preceded by a determined movement among the colored residents of Harlem to obtain employment for some of their number in the many stores which owe their very existence to Negro patronage. The Kress store was one of these; it had only two or three Negroes in its employ when the storm broke.

As Jervis Anderson observes of 1935 in his informative study, This Was Harlem, 1900-1950, It was the first major riot in the history of black Harlem, and it would not be the last. However, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., offered a different interpretation: It was not a riot; it was an open, unorganized protest against empty stomachs, overcrowded tenements, filthy sanitation, rotten foodstuffs, chiseling landlords and merchants, discrimination on relief, disfranchisement, and against a disinterested administration. He insisted, It was not caused by Communists.

The U.S. has witnessed two great waves of race-based incidents: the first around the time of the World War I and the second amidst the Vietnam War. The first wave lasted from 1917 to 1921 and involved mostly Whites attacking Blacks. It reflected the social dislocation precipitated by industrialization, the Great Migration and the war.

The second wave lasted from 1964 to 1968 and reflected mostly African-Americans venting their rage against local conditions including private property and the police much determined by mounting urban dislocation, institutional racism and the war.

The first wave included the following:

The May 1919 East St. Louis, IL, confrontations was precipitated by the hiring of some 500 African-Americans to break a strike by White workers at the Aluminum Ore Company. The initial riot saw White mobs attack Blacks throughout the city, including pulling them from trolley and beating them; the governor called in the National Guard to reestablish order. A second outbreak followed in July when Whites again attacked Blacks, including women and children; the victims of the violence were beaten, shot and lynched, and Black homes and businesses were burned.

In August 17, a very different “riot” took place in Houston, TX. Two White police entered the home of a Black woman, seized, beat and arrested her for no apparent reason. A Black U.S. soldier who was passing by tried to determine what was happening and was similarly assaulted and arrested. Later in the day, a fellow Black soldier went to the police station to free his friend and he was also beaten and arrested. This led 156 black soldiers from the all-Black Third Battalion, 24th Infantry, stationed at nearby Camp Logan, to march on the city; and they came armed to the teeth.

Twenty people were killed, including four soldiers and four policemen. After the soldiers were disarmed, they were court martialled and 13 were hung.

James Weldon Johnson, the Harlem Renaissance writer, dubbed the race attacks of the summer of 1919, Red Summer, due to all the Black blood that flowed. Tensions mounted in the aftermath of WW-I as returning White soldiers confronted labor competition from recently arrived Blacks from the South and incidents took place in 26 cities including eruptions in: Washington, DC, Chicago, IL, Omaha, NB, Knoxville, TN, Longview, TX, and Phillips County, AK.

The Tulsa, OK, incident of 1921 was the worst civil disturbance of the First wave. African-American residents, especially in the prosperous Greenwood neighborhood, were set upon, their homes and businesses burned and looted.

The state National Guard was called in and an estimated 6,000 Blacks were arrested and Greenwood was destroyed. The first official inquiry claimed 26 Blacks and 10 Whites died; however, a Tulsa Race Riot Commission report of 2000 estimated that 300 people died.

Four decades later, the character of riots changed. The Second wave of saw African-Americans initiate fierce rebellions against urban racial injustice.

The eras uprising began inauspiciously in New York City in July 1964 in a standoff between James Powell, African-American teenager, and Thomas Gilligan, a police lieutenant.

After a chase, the youth allegedly pulled a knife and slashed the officer who, in turn, pulled his revolver, shot and killed Powell. At least two witnesses interviewed in a New York Times article claimed they did not see a knife and that the shooting appeared unjustified.

The incident took place on East 70th Street and fueled uprising that lasted six last days and involved throwing Molotov cocktails and police firing more then 2,000 shots. Remarkably, only one person died.

During the hot August 11-17, 1965, period, the Watts section of Los Angeles erupted in violent protest. An initial confrontation between a Black motorist and a White highway patrolman was followed by a scuffle that drew a crowd incensed by the mistreatment of the motorist and his fellow passengers.

An estimate 30,000 people filled area streets, throwing rocks at police, attacking White residents and setting buildings aflame. Martial law was declared and a curfew implemented; 4,000 National Guard troops were called to assist some 1,600 local police. The incident left 34 people dead, more than 1,000 injured and about 4,000 under arrest.

In July of the following year, Newark, NJ, was the scene of the next major incident. The arrest and beating of a Black taxi driver combined with the local polices refusal to address civil-rights activists demands — precipitated the confrontations. Peaceful protests turned violent in the face of harsh police reactions, with residents throwing bottles, rocks and Molotov cocktails at the local police station where the driver was held. Three days of activity led the governor to call in the National Guard that engaged in a form of urban warfare to quell the civil disturbance. Some 1,500 people were arrested, 725 injured and 26 killed; property damage was estimated at $10 million.

The Second wave of confrontations came to a head in 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King. In April, King had gone to Memphis, TN, to support striking African-American sanitation workers and was shot while staying at the Lorraine Motel. Kings killing precipitated protests in more then 110 U.S. cities.

In Washington, DC, some 20,000 people participated in widespread looting, arson and attacks on police that reached two blocks from The White House. Local police, the National Guard and Marines were required to put down the mass rage that left more than 1,200 buildings destroyed, 12 people dead and an estimated $27 million in damages.

In Baltimore, local police, state National Guard and some 5,000 federal troops were called in to restore order; some 4,500 people were arrested, 700 injured and seven killed.

A similar story played out in Chicago where a 28-block area of the West Side was engulfed, with stores and homes looted, buildings set on fire and violent confrontations between residents and police. About 10,000 police officers and 6,500 National Guardsmen were deployed; 2,150 were arrests and 11 people killed.

Since the 1960s, sporadic incidents have taken place. In August 1991, confrontations broke out in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York, between Hasidic Jews and Blacks –both African-Americans and Caribbeans– following a car crash. The car was driven by a Hasidic resident and resulted in the death of two Black children. In the three-day confrontations that followed, a Black resident stabbed and killed a visiting Hasid while some 40 civilians and 150 officers were injured.

In 1992, an all-White jury acquitted Los Angeles police officers in the violent assault on Rodney King, an incident that was videotaped and repeatedly aired on television. The decision precipitated six days of mass protest in predominately African-American areas of Los Angeles, leading to widespread lootings and standoffs with police. Thousands were arrested and 50 died; property damage was estimated at $1 billion.

The website, killedbypolice.net, documents nearly 2,000 (1,893) police killings of civilians in 2014, and in 2015, 787 as of Aug. 29. They include Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO; Eric Garner in Staten Island, NY; and Walter Scott in North Charleston, SC; as well as incidents in Madison, WI; Los Angeles, CA; Phoenix, AZ; Pasco, WA; and Baltimore, MD; among many others.

Looking back at the history of 20th century incidents, its remarkable that nothing on the order of uprising of 1960s has yet taken place.

The killing of an African-American man or woman or another person-of-color or the failure of local prosecutors to indict the apparent police officer or officers involved in the killing precipitated the current wave of popular protests taking place across the country.

The challenging question is why these protests have with a couple of isolated exceptions (e.g., Baltimore) not reached the level of violence of the Second wave or other late-20th century uprisings such as LAs Rodney King incident? Why have they remained relatively isolated and contained like the Harlem one of 1935?

The 1935 Harlem incident signaled a shift in riots from race wars (i.e., majority Whites assailing minority Blacks) to urban rebellions; inner-city African-Americans protesting racial segregation.

None of the incidents of the 20th and 21st century compare to the nationwide outrage witnessed in the wake of Dr. Kings assassination.

It involved the principle leader of the civil-rights movement and fueled outrage in more than a 100 cities. Nor have the protests since 2012 witnessed the same level of rebellion seen in Watts, Newark or following the Rodney King decision.

But does quantity at some point turn into quality?

Will the simmering racial cauldron of social outrage, fueled by thousands of police killings as much as by institutionalized racism, explode into a nationwide crisis not dissimilar to what took place after Kings assassination?

This is the unanswered question.

David Rosen is the author of the forthcoming, Sex, Sin & Subversion: The Transformation of 1950s New Yorks Forbidden into Americas New Normal (Skyhorse, 2015). He can be reached at [email protected] check out www.davidrosenwrites.com